by Fabio Roli and Matteo Mauri

Heading image by Rock'n Roll Monkey on Unsplash

Marvin Minsky, one of the fathers of Artificial Intelligence, defined intelligence as a "suitcase word" which can lead to ambiguity and confusion, if we do not clarify in what sense we speak of "intelligence". For the same reason, writing a non-technical article on Artificial Intelligence is always a risk, especially for a technical person, and especially nowadays that the term “Artificial Intelligence” is, more than ever, a "suitcase" in which everybody puts a bit of everything. In this post, we will try to unpack this suitcase and to reorder the stuff inside, at least a little.

Short history of Artificial Intelligence

Although the investigation about intelligent machines was born much earlier than the invention of modern electronic computers [1], the experts mostly agree that the term "Artificial Intelligence" (AI) was firstly introduced during the legendary Dartmouth "workshop” (August 1955), when a small group of scientists, now considered the fathers of AI, had set the goal of simulating some aspects of human intelligence through a computer [2].

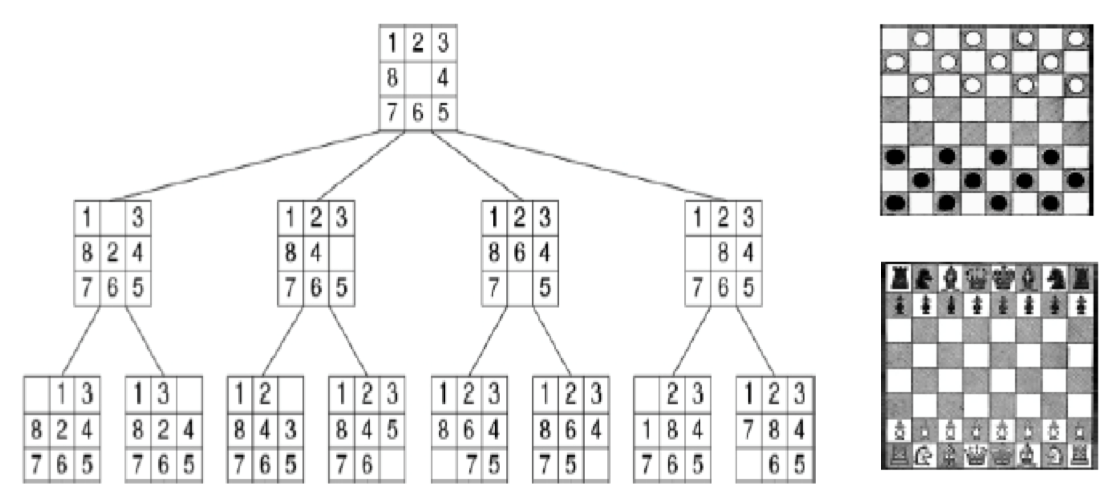

In the first twenty years of AI history (1950-1970), “intelligence” was considered as a product of "logical" and "symbolic" reasoning, and reasoning was implemented by computers with search algorithms (Figure 1). The aim was to simulate human intelligence through solving simple games and proving theorems. It soon became clear that these algorithms could not be used to solve real problems such as the movement of a robot in an unknown room: an enormous "knowledge" of the real world would have been needed to avoid a "combinatorial" explosion of the problem to solve.

Fig .1: Intelligence as logical problem solving

In the 80s it was decided pragmatically to limit the AI scope to specific tasks, such as the simulation of intelligent decision making for the medical diagnosis of particular pathologies. This was the “era” of the so-called “expert systems”, capable of successfully simulating the intelligence of a human expert in narrow and well-defined fields [3].

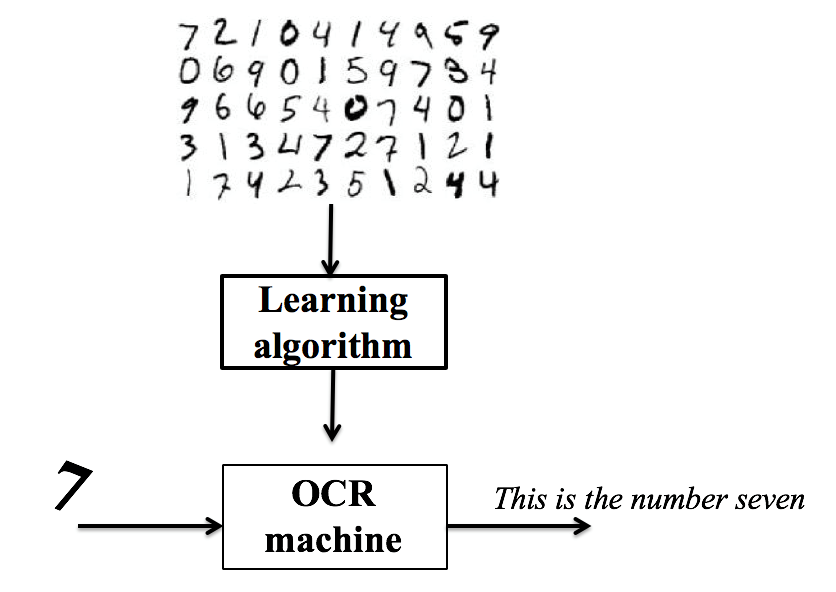

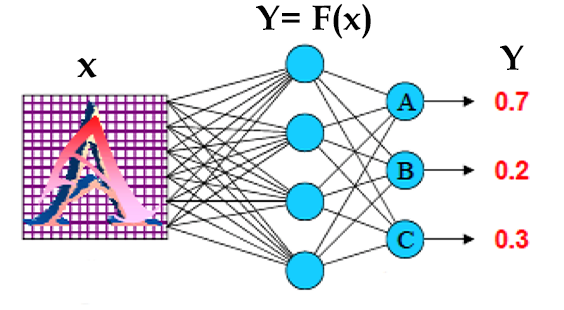

At the same time, it gradually became clear that some intelligent behaviors, like recognition of written text, could not be realized with an algorithm built with a sequence of instructions previously defined. Instead it was possible to collect multiple examples of the objects to be recognized, and using algorithms that could learn the essential characteristics of these objects (Figure 2).

Fig. 2: Automatic learning from examples (“machine learning”)

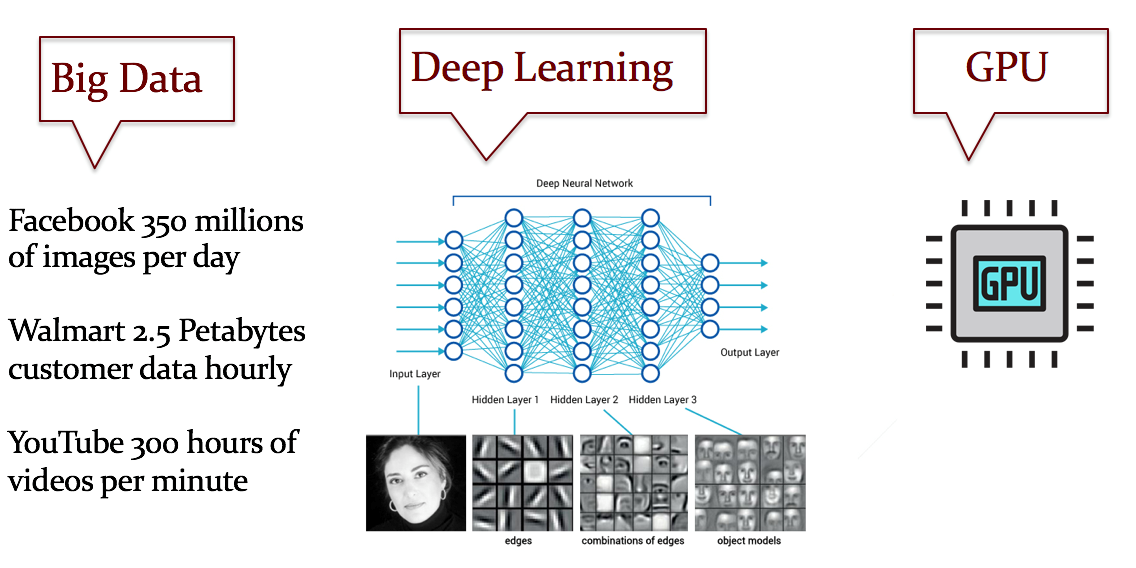

It was the birth of what we now call "machine learning": the computer learning process could be formulated as a mathematical optimization problem and explained with probabilistic and statistical models [4]. Some of the learning algorithms that were used to simulate the human brain were called "artificial neural networks" (Figure 3). In its first four decades, AI has gone through periods of euphoria followed by periods of unfulfilled expectations ("AI winter"). At the beginning of the 2000s the progressive focus on specific problems and the increase of investments led to the first historical achievements: in some very specific tasks AI systems got better performances than humans [5]. Up to the current phase, in which the enormous availability of data ("big data") together with the growing computational power of machines has allowed to fully exploit all the research done over previous decades inside the Deep Learning models, giving birth to what some consider the fourth industrial revolution (Figure 4).

Fig. 3: Artificial neural networks

Fig. 4: The “deep learning” paradigm

What does “intelligent machine” mean?

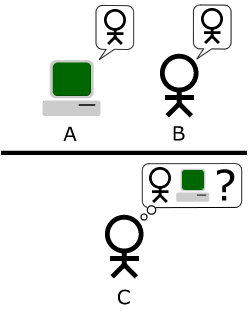

After the invention of computers, the discussion on the nature of the intelligence, that had engaged philosophers for thousands of years, took the form of the title of this section. Already a few years before the Dartmouth workshop, one of the historical fathers of AI, Alan Turing, had asked himself this question and, while seeking an answer, he had proposed a "test", now known as the "Turing test", in order to evaluate the machine intelligence [6]. Suppose we put together in a room a human and a computer that claims to be intelligent. Another human, a "judge", can communicate with them in written and spoken form, but without seeing them. The judge does a series of questions to the two interlocutors and then decides who is human and who is not (Figure 5). The judge's mistake is the proof of the machine's intelligence; it is the proof that the machine is indistinguishable from an intelligent human. This definition of intelligence solves many of the ambiguities that can be encountered in defining what intelligence is. We do not pretend that the computer thinks like us, just as we did not demand that planes fly like birds. We are satisfied that the computer cannot be distinguished from a human for a series of tasks that require what we call intelligence. The complexity and vastness of the tasks required distinguish what is called "Narrow AI" (limited artificial intelligence, e.g. the current chess-playing computers) from the "General AI" of future systems that should be able to show an intelligence on a human level, or higher, for a wide range of tasks.

Fig. 5: the Turing test (“The imitation game”)

In the next article, “Artificial Intelligence: past, present and future. Part II - The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”, that will be published soon in this blog, we will talk again about Artificial Intelligence, using a leitmotiv that is a small tribute to the famous movie by Sergio Leone. We are not the first to use this leitmotiv to talk about Artificial Intelligence. AI certainly has "good", "ugly" and "bad" aspects; highlighting these aspects can help to understand what is Artificial Intelligence today. Always bearing in mind that, as in the case of the three characters of Sergio Leone’s movie, the good, the bad and the ugly cannot be clearly separated.

Acknowledgments. An Italian version of this article has been published in [7]. The authors thank “Associazione Italiana per la Sicurezza Informatica” for permission to reuse the contents.

[1] Just think about the Renato Cartesio’s dualism between mind and body

[2] Dartmouth Research Project: https://www.aaai.org/ojs/index.php/aimagazine/article/view/1904

[3] https://www.britannica.com/technology/expert-system

[4] M. Gori, Machine Learning: a constraint-based approach, Morgan Kaufmann, 2017

[5] https://www.scientificast.it/uomo-vs-macchina-watson-gioca-jeopardy/

[6] A. Turing, Computing Machinery & Intelligence, Mind, Vol. 59(236), 1950

[7] F. Roli, Intelligenza Artificiale: il Buono, il Brutto, il Cattivo, Rapporto Clusit 2019 sulla Sicurezza ICT in Italia, 2019 (in Italian)